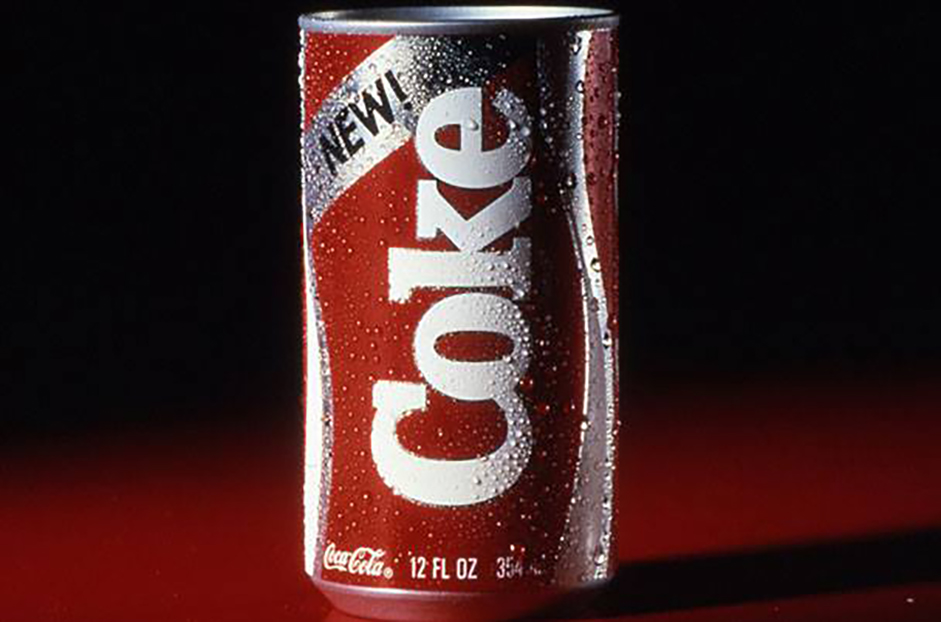

In spite of the fact that tests showed the new formula tasted better than old Coke, customers believed otherwise. The New Coke failure happened because Coke tried to be something it wasn't.

Many people consider the introduction of New Coke as the biggest marketing blunder of the 20th century, so the story behind the giant mistake is fascinating and informative.

By 1985, war was raging in the cola duopoly, Coke and Pepsi. In the late ’50s, Coke outsold Pepsi by more than five to one. It built its dominance with one of the most powerful expressions of brand leadership ever, with three little words: the real thing.

One of the ways to position a No. 2 in a category is to go against the No. 1. That’s the strategy Pepsi used against Coke. Pepsi thought that if Coke was the “original,” it was the choice of older people. Pepsi had to go against that position.

Pepsi’s solution was to focus on younger people with the theme, “Pepsi, The Choice of a New Generation.” That began in the early ’60s, and it worked. Pepsi cut Coke’s lead in half.

What was Coke to do? They couldn’t give up their “It’s the real thing” position first used as its slogan in 1942. Pepsi found an inherent weakness in Coke’s strength. Pepsi put Coke on the ropes.

In the ’70s, Pepsi came out with the “Pepsi Challenge.” This was a series of blind taste tests that found more people preferred the sweeter taste of Pepsi. Pepsi communicated these findings with lots of television commercials casting good- and happy-looking young people. Coca-Cola’s headquarters in Atlanta trembled with worry. It’s own research verified Pepsi’s claim.

Many remember the last line of Pepsi’s tune, “You’ve got a lot to live ... and Pepsi’s got a lot to give.” This inspired Coke to do a similar “hip” campaign, “I’d Like to Teach the World to Sing in Perfect Harmony.” Both campaigns were examples of great advertising from a period we now call “the Don Draper” era, a reference to the popular “Mad Men” TV series.

Pepsi made gains throughout the ’70s and into the early ’80s. It began to outsell Coke in supermarkets. It was bad enough to lose the taste tests, but market share loss, too? Something had to be done.

As Coke saw it, the problem was with its product. So it did what seemed to make the most logical sense: It began working on a new formula. It was the first recipe change since 1903, when it removed cocaine.

After a quarter-million taste tests and almost two years, they had a formula that beat Pepsi in the blind taste tests.

To beat Pepsi in the marketplace, Coke couldn’t have two directly competing colas on the shelf, so it decided to stop producing the original Coca-Cola and to introduce New Coke. That, they thought, would solve their big problem with the Pepsi Challenge. They would now beat Pepsi with a better-tasting cola.

Disastrous failure

New Coke was introduced April 23, 1985. It was a disaster. Coke drinkers responded with unrelenting backlash, a serious revolt and even a boycott.

The company’s switchboards were soon drowning in nearly 10,000 calls a day from irate customers.

New Coke became a worldwide story, but for all the wrong reasons. New Coke failure was criticized as the biggest marketing blunder of all time. On July 11, 1985, less than three months later, the company brought back the original Coke.

Legendary brand designer Walter Landor said products are created in the factory, but brands are created in the mind. Coke learned this the hard way. Credit Coca-Cola for quickly acknowledging its failure and making a U-turn.

If you tell the world you are the “Real Thing,” then you can’t come up with the “New Real Thing.” Coke’s attempt to reposition itself around a “new” idea was counter to the idea it owns in our minds: the “original.” A brand can only stand for one cohesive idea. Coke undermined its own position.

Upon switching back to its original formula, its sales and market share went up higher than before. ABC News anchor Peter Jennings broke into “General Hospital” to report Coca-Cola was moving to put its original soft-drink formula back on the market. Some theorized the whole thing was a clever marketing ploy. A key Coke executive responded, “The truth is we are not that dumb, and we are not that smart.”

Coke’s nightmare was over. It realized who it is. It’s about heritage. It is the original. The real thing. So it can’t also be the new thing.

Perception is stronger than reality. In spite of the fact that tests showed the New Coke tasted better than old Coke, customers believed otherwise.

Perception affects taste in the same way it affects all human judgment.

The battle takes place in the mind. Some argue there are only perceptions. The perception is the reality.

As Jack Trout, the man who coined the term “positioning,” has stated so succinctly, “Marketing is a battle of perceptions, not products.” New Coke failure was due to negative perceptions.